Brexit, for once some facts.

- Thread starter flecc

- Start date

You really are a proper mouth breathing troll aren't you.One more completely off-topic.

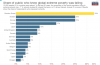

But Tom and his socialist-leaning friends might want to take note of this too:

View attachment 28207

Excellent article (completely ON-topic) about Brexit - the current situation.

I realise some of your are not interested in the facts - so you can skip this.

(split into a few posts as there is a limit to size)

PART ONE:

"There are only 45 parliamentary working days before Britain leaves the European Union on March 29.

In that time MPs and peers have the power to set the terms of the country’s departure by either endorsing Theresa May’s Brexit deal or setting an alternative course.

If they don’t, Britain will still leave the EU but without a deal and in a manner with no precedent. That is not to say Britain and Europe have not planned for such an outcome.

Thousands of man-hours in Whitehall and Brussels have been spent war-gaming scenarios and drawing up contingency plans to minimise disruption resulting from the end of 40 years of political, legal and economic co-operation. There is only so much that can be done, however, because neither side has an accurate idea of what it will face.

To opponents of Brexit a no-deal scenario would be little short of Armageddon. Supermarket shelves would empty, sterling would crash, firms would go out of business and patients would be denied life-saving medication.

Supporters accept that there will be disruption but it would be temporary and mitigated by new legal freedoms and opportunities born of being completely outside the EU’s orbit.

So what are the most realistic best and worst-case scenarios for individuals, businesses and sectors of the economy, and, as importantly, what are the factors that each side cannot plan for?

FREIGHT TRANSPORT

Worst case:

At present an unlimited number of hauliers based in the UK can ship goods across the EU and about 38,000 UK-registered goods vehicles, carrying 20 million tonnes of freight a year, travel to the continent. Without a deal operators may have to apply for an international road haulage permit for each vehicle and Britain’s quota is only 4,000. The Department for Transport has announced plans for a “lorry lottery” to allocate the permits and business leaders have warned that the shortfall would result in severe disruption to cross-channel trade.

Hauliers may find it hard to get a permit to deliver freight to the Continent.

Best case:

The EU has announced it will ensure that freight transport can continue in the immediate aftermath of a no-deal Brexit to limit the impact on 50 million tonnes of freight that travels from Europe to the UK. Britain has secured membership of the Common Transit Convention after Brexit, which means that hauliers will need permits only for their end destination, not the countries through which they pass.

Unknown factor:

Bilateral transport agreements cannot be negotiated until after Brexit and no one knows how long these will take.

CITIZENS’ RIGHTS

Worst case:

The UK has said it will guarantee the rights of the EU citizens living in Britain broadly in line with the commitments already made in the withdrawal agreement. However, without a deal the UK is reliant on each EU member state reciprocating.

The European Commission has urged all countries to “take measures so that all UK nationals will continue to be considered as legal residents of that member state without interruption”. Some conceivably might choose not to, or offer less generous terms than those offered by Britain.

Best case:

Members states move swiftly to provide legal certainty and the same rights to all British citizens living in their jurisdictions. Most countries are putting legislation into effect to ensure that happens.

Unknown factor:

Pensions, social security payments and the healthcare of expats are also affected by Brexit. UK citizens may find that not all their existing rights are safeguarded in a no-deal scenario but that will vary on a country by country basis.

AGRICULTURE

Worst case:

Exports of food and drink from the UK to Europe are worth £13.2 billion a year, so any disruption to trade could be devastating for British farmers. In 2014, 82 per cent of the UK’s total exported meat and 75 per cent of its dairy produce went to the EU. This means that any delays could rapidly slow the entire supply chain in both directions, forcing Europeans to source food elsewhere and putting farmers’ livelihoods at risk. This is especially true in Northern Ireland where food, beverages and tobacco account for 49 per cent of the cross-border manufacturing trade, and a quarter of all milk produced in the province is exported for processing south of the border. About 90 per cent of Welsh lamb exports go to Europe. Outside the single market all food and agricultural products crossing between Britain and Europe would, by law, be subject to veterinary and food safety checks. In a no-deal scenario the UK would need to hire more vets to process export health certificates proving that food and livestock comply with the appropriate EU standards and regulations.

Best case:

It is unlikely that the EU would want to impose draconian checks in the short-term as it would damage consumers in a tangible and dramatic way. They are more likely to quickly list the UK as a third country to ensure there is no abrupt ceasing of imports in either direction. However, it is hard for the EU to say that it probably will not impose checks, for fear that it could incentivise Conservative ministers to push for a “managed no deal”.

Unknown factor:

Even if it is in Britain’s and the EU’s interests to avert checks initially, that may not be sustainable in the medium term if regulations and standards diverge. Both the UK and EU member states have a shortage of vets to process export health certificates. The Dutch government has used the bloc’s rules on free movement to recruit staff from Eastern Europe. The UK cannot do the same."

TO BE CONTINUED

I realise some of your are not interested in the facts - so you can skip this.

(split into a few posts as there is a limit to size)

PART ONE:

"There are only 45 parliamentary working days before Britain leaves the European Union on March 29.

In that time MPs and peers have the power to set the terms of the country’s departure by either endorsing Theresa May’s Brexit deal or setting an alternative course.

If they don’t, Britain will still leave the EU but without a deal and in a manner with no precedent. That is not to say Britain and Europe have not planned for such an outcome.

Thousands of man-hours in Whitehall and Brussels have been spent war-gaming scenarios and drawing up contingency plans to minimise disruption resulting from the end of 40 years of political, legal and economic co-operation. There is only so much that can be done, however, because neither side has an accurate idea of what it will face.

To opponents of Brexit a no-deal scenario would be little short of Armageddon. Supermarket shelves would empty, sterling would crash, firms would go out of business and patients would be denied life-saving medication.

Supporters accept that there will be disruption but it would be temporary and mitigated by new legal freedoms and opportunities born of being completely outside the EU’s orbit.

So what are the most realistic best and worst-case scenarios for individuals, businesses and sectors of the economy, and, as importantly, what are the factors that each side cannot plan for?

FREIGHT TRANSPORT

Worst case:

At present an unlimited number of hauliers based in the UK can ship goods across the EU and about 38,000 UK-registered goods vehicles, carrying 20 million tonnes of freight a year, travel to the continent. Without a deal operators may have to apply for an international road haulage permit for each vehicle and Britain’s quota is only 4,000. The Department for Transport has announced plans for a “lorry lottery” to allocate the permits and business leaders have warned that the shortfall would result in severe disruption to cross-channel trade.

Hauliers may find it hard to get a permit to deliver freight to the Continent.

Best case:

The EU has announced it will ensure that freight transport can continue in the immediate aftermath of a no-deal Brexit to limit the impact on 50 million tonnes of freight that travels from Europe to the UK. Britain has secured membership of the Common Transit Convention after Brexit, which means that hauliers will need permits only for their end destination, not the countries through which they pass.

Unknown factor:

Bilateral transport agreements cannot be negotiated until after Brexit and no one knows how long these will take.

CITIZENS’ RIGHTS

Worst case:

The UK has said it will guarantee the rights of the EU citizens living in Britain broadly in line with the commitments already made in the withdrawal agreement. However, without a deal the UK is reliant on each EU member state reciprocating.

The European Commission has urged all countries to “take measures so that all UK nationals will continue to be considered as legal residents of that member state without interruption”. Some conceivably might choose not to, or offer less generous terms than those offered by Britain.

Best case:

Members states move swiftly to provide legal certainty and the same rights to all British citizens living in their jurisdictions. Most countries are putting legislation into effect to ensure that happens.

Unknown factor:

Pensions, social security payments and the healthcare of expats are also affected by Brexit. UK citizens may find that not all their existing rights are safeguarded in a no-deal scenario but that will vary on a country by country basis.

AGRICULTURE

Worst case:

Exports of food and drink from the UK to Europe are worth £13.2 billion a year, so any disruption to trade could be devastating for British farmers. In 2014, 82 per cent of the UK’s total exported meat and 75 per cent of its dairy produce went to the EU. This means that any delays could rapidly slow the entire supply chain in both directions, forcing Europeans to source food elsewhere and putting farmers’ livelihoods at risk. This is especially true in Northern Ireland where food, beverages and tobacco account for 49 per cent of the cross-border manufacturing trade, and a quarter of all milk produced in the province is exported for processing south of the border. About 90 per cent of Welsh lamb exports go to Europe. Outside the single market all food and agricultural products crossing between Britain and Europe would, by law, be subject to veterinary and food safety checks. In a no-deal scenario the UK would need to hire more vets to process export health certificates proving that food and livestock comply with the appropriate EU standards and regulations.

Best case:

It is unlikely that the EU would want to impose draconian checks in the short-term as it would damage consumers in a tangible and dramatic way. They are more likely to quickly list the UK as a third country to ensure there is no abrupt ceasing of imports in either direction. However, it is hard for the EU to say that it probably will not impose checks, for fear that it could incentivise Conservative ministers to push for a “managed no deal”.

Unknown factor:

Even if it is in Britain’s and the EU’s interests to avert checks initially, that may not be sustainable in the medium term if regulations and standards diverge. Both the UK and EU member states have a shortage of vets to process export health certificates. The Dutch government has used the bloc’s rules on free movement to recruit staff from Eastern Europe. The UK cannot do the same."

TO BE CONTINUED

View attachment 28204[/QUOTE][QUOTE - KudosDave] Rudd seems to be a genuine lady ,the ERG would hate her-who cares!!

I think Amber Dudd is having difficulty with words like resign and referendum. She thinks resign means return after a few weeks and that referendum means, repeat until the desired outcome is achieved.

PART TWO:

AVIATION

Worst case:

Without legal measures being taken by both sides before March 29, flights between Britain and European destinations could be disrupted when the UK leaves the bloc. Some lobbyists have even suggested that air traffic could be grounded, although that claim is heavily disputed. Flights from the UK to other destinations could also be affected if the right to fly is based on an existing EU-wide agreement.

Best case:

The European Commission announced yesterday that it would table legislation in the new year to allow British airlines access to its airspace and airports for up to 12 months, but with restrictions on transit flights. The British government has prepared the legislation necessary to reciprocate. Both sides say they are now reasonably confident that disruption can be kept to a minimum.

Unknown factor:

The UK’s flying rights to countries such as India, Israel and Vietnam are based on European Union agreements. These will have to be renegotiated and ratified by March to prevent potential disruption. Any EU dispensations will also be temporary and Britain will have to negotiate a long-term aviation deal with the EU.

TRADE DEALS

Worst case:

About 40 of the UK’s trade deals with countries outside Europe are dependent on its membership of the bloc and will fall away in the event of no deal. They include important export markets such as South Korea, Canada and South Africa. The government said last October that these would be transferred into bilateral agreements in time for March in case of no deal. However, just one trading partner, Switzerland, has so far formally agreed to replicate its EU deal for Britain after Brexit. If this process is not completed by March 29 then British exporters could find themselves suddenly paying World Trade Organisation tariffs in key markets, disrupting trade and putting Britain at a significant competitive disadvantage.

Best case:

A number of countries, including Canada and South Africa, have committed to replicating their trade deals by the March deadline even if they have not yet been formally agreed.

Unknown factor:

Until they are published we will not know whether Britain’s trading partners have forced concessions as the price of getting the deals agreed in time. International trade negotiations are unsentimental and, given Britain’s weak negotiating position, the new deals could be less favourable than the current arrangements.

MEDICINE

Worst case:

Every month 37 million packs of medicine enter the UK from the rest of the EU and the pharmaceutical industry is spending hundreds of millions of pounds on extra warehouses to stockpile supplies. However, there is a shortage of the cold storage needed to house modern biological medicines. Delays crossing the Channel are considered the biggest risk to medicine supplies and if disruption continues then stocks built up to last six weeks may not be enough.

Best case:

This is an area of contingency planning that has had the most attention, and early-warning systems are in place to identify shortages before they become critical. The EU would also not want to see drug shortages — and the complex pharmaceutical supply chain would affect drug availability in other European countries.

Unknown factor: Stockpiling plans have been based on normal levels of demand but such supplies could run out much faster if patients try to hoard medicines in fear they could run out. This is why the government has issued rules to allow ministers to control what pharmacies can supply in a worst-case scenario.

TRAVEL

Worst case:

British travellers who want to hire a car in Europe could be turned away unless they have a £5.50 international driving licence that must be applied for in advance from a post office; passengers could also be refused travel if they have less than six months on their passport and will need a US-style visa waiver. The maximum stay for a UK visitor will be three months. Anyone wishing to take a pet will need to make preparations up to four months in advance. Britons travelling to the EU will no longer be covered by pan-European healthcare that allows them to be treated in hospitals free of charge. Hefty mobile phone roaming charges may return.

Best case:

Car rental firms may choose not to rigidly enforce the rules. The government is also hopeful that eventually the EU will recognise Britain as a “listed third country” for pet passports which would result in little change to the current arrangements. Ministers have brought forward legislation to allow the European healthcare insurance card to continue to operate in the UK after Brexit and are hoping that other EU countries will reciprocate. Ministers have also said that in the case of a no-deal Brexit the government would legislate to cap roaming surcharges at £45 per month.

Unknown factor:

Areas such as immigration control and access to healthcare are decided at a national level so the UK will have to negotiate reciprocal deals with each of the 27 member states. These could vary by country, causing confusion for travellers.

AVIATION

Worst case:

Without legal measures being taken by both sides before March 29, flights between Britain and European destinations could be disrupted when the UK leaves the bloc. Some lobbyists have even suggested that air traffic could be grounded, although that claim is heavily disputed. Flights from the UK to other destinations could also be affected if the right to fly is based on an existing EU-wide agreement.

Best case:

The European Commission announced yesterday that it would table legislation in the new year to allow British airlines access to its airspace and airports for up to 12 months, but with restrictions on transit flights. The British government has prepared the legislation necessary to reciprocate. Both sides say they are now reasonably confident that disruption can be kept to a minimum.

Unknown factor:

The UK’s flying rights to countries such as India, Israel and Vietnam are based on European Union agreements. These will have to be renegotiated and ratified by March to prevent potential disruption. Any EU dispensations will also be temporary and Britain will have to negotiate a long-term aviation deal with the EU.

TRADE DEALS

Worst case:

About 40 of the UK’s trade deals with countries outside Europe are dependent on its membership of the bloc and will fall away in the event of no deal. They include important export markets such as South Korea, Canada and South Africa. The government said last October that these would be transferred into bilateral agreements in time for March in case of no deal. However, just one trading partner, Switzerland, has so far formally agreed to replicate its EU deal for Britain after Brexit. If this process is not completed by March 29 then British exporters could find themselves suddenly paying World Trade Organisation tariffs in key markets, disrupting trade and putting Britain at a significant competitive disadvantage.

Best case:

A number of countries, including Canada and South Africa, have committed to replicating their trade deals by the March deadline even if they have not yet been formally agreed.

Unknown factor:

Until they are published we will not know whether Britain’s trading partners have forced concessions as the price of getting the deals agreed in time. International trade negotiations are unsentimental and, given Britain’s weak negotiating position, the new deals could be less favourable than the current arrangements.

MEDICINE

Worst case:

Every month 37 million packs of medicine enter the UK from the rest of the EU and the pharmaceutical industry is spending hundreds of millions of pounds on extra warehouses to stockpile supplies. However, there is a shortage of the cold storage needed to house modern biological medicines. Delays crossing the Channel are considered the biggest risk to medicine supplies and if disruption continues then stocks built up to last six weeks may not be enough.

Best case:

This is an area of contingency planning that has had the most attention, and early-warning systems are in place to identify shortages before they become critical. The EU would also not want to see drug shortages — and the complex pharmaceutical supply chain would affect drug availability in other European countries.

Unknown factor: Stockpiling plans have been based on normal levels of demand but such supplies could run out much faster if patients try to hoard medicines in fear they could run out. This is why the government has issued rules to allow ministers to control what pharmacies can supply in a worst-case scenario.

TRAVEL

Worst case:

British travellers who want to hire a car in Europe could be turned away unless they have a £5.50 international driving licence that must be applied for in advance from a post office; passengers could also be refused travel if they have less than six months on their passport and will need a US-style visa waiver. The maximum stay for a UK visitor will be three months. Anyone wishing to take a pet will need to make preparations up to four months in advance. Britons travelling to the EU will no longer be covered by pan-European healthcare that allows them to be treated in hospitals free of charge. Hefty mobile phone roaming charges may return.

Best case:

Car rental firms may choose not to rigidly enforce the rules. The government is also hopeful that eventually the EU will recognise Britain as a “listed third country” for pet passports which would result in little change to the current arrangements. Ministers have brought forward legislation to allow the European healthcare insurance card to continue to operate in the UK after Brexit and are hoping that other EU countries will reciprocate. Ministers have also said that in the case of a no-deal Brexit the government would legislate to cap roaming surcharges at £45 per month.

Unknown factor:

Areas such as immigration control and access to healthcare are decided at a national level so the UK will have to negotiate reciprocal deals with each of the 27 member states. These could vary by country, causing confusion for travellers.

I fully agree for JCB, a great company for this country to be very proud of.No deal? No problem: From the Chairman of JCB

My problem is how short we are of such gems and the often despair I felt when working for some of our poorer managed examples.

.

FINAL PART:

DIVORCE BILL

Worst case:

Britain could end up paying more into the EU budget than under the financial settlement in the withdrawal treaty. The impact of no deal on the Brussels budget is low in 2019 because of the structure of the bloc’s financing, so the shortfall is only expected to be some €3 billion. The EU will demand payments in return for longer term measures, such as on road haulage of freight or aviation, and to ensure deals Britain would still have to make payments at least equivalent to the financial settlement in the draft withdrawal treaty — and possibly more. All 27 EU countries will have vetoes over many of the areas under negotiation and, according to senior Brussels sources, “will not even get around the table unless the money is there to stop a spending shortfall”.

Best case:

Money is seen as the key to unlocking a positive no-deal scenario by some hardline Brexit supporters. The EU will negotiate a good trade deal with Britain to avoid facing budget shortfalls of some €18 billion by the end of 2020 and a longer term loss of more than €20 billion in other payments. Money will be a lever for Britain because countries that already pay large sums into the EU, such as Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, Finland and Sweden, will make concessions or else face politically toxic increases in their payments.

Unknown factor:

It is unclear exactly how domestic politics would play out both in the UK and the Netherlands. In Britain pressure to pay nothing could result in worse long-term outcomes for the UK while, conversely, in the longer term if Britain was prepared to continue to pay into Brussels budgets it would win significant market access for less than its current £9 billion-a-year net contribution.

DATA

Worst case:

Huge amounts of personal data flow between computer servers in the European Union and Britain every day and the legal basis for much of this transfer will fall away in a no-deal Brexit. These flows of data allow online banking, e-commerce and the back-office functions of thousands of businesses to continue. In a no-deal scenario it will become illegal for European bodies to transfer such personal information to the UK. The EU has not yet made any contingency plans.

Best case:

The UK has said that it will legally recognise the EU as an “adequate” jurisdiction to hold the data of British citizens after Brexit. The EU has yet to reciprocate but it is unlikely to want to damage businesses that rely on UK servers to process information.

Unknown factor: The General Data Protection Regulation that governs the handling of personal data in the EU is policed by individual member states, which could interpret the rules differently. Any “patch” could be open to legal challenge."

DIVORCE BILL

Worst case:

Britain could end up paying more into the EU budget than under the financial settlement in the withdrawal treaty. The impact of no deal on the Brussels budget is low in 2019 because of the structure of the bloc’s financing, so the shortfall is only expected to be some €3 billion. The EU will demand payments in return for longer term measures, such as on road haulage of freight or aviation, and to ensure deals Britain would still have to make payments at least equivalent to the financial settlement in the draft withdrawal treaty — and possibly more. All 27 EU countries will have vetoes over many of the areas under negotiation and, according to senior Brussels sources, “will not even get around the table unless the money is there to stop a spending shortfall”.

Best case:

Money is seen as the key to unlocking a positive no-deal scenario by some hardline Brexit supporters. The EU will negotiate a good trade deal with Britain to avoid facing budget shortfalls of some €18 billion by the end of 2020 and a longer term loss of more than €20 billion in other payments. Money will be a lever for Britain because countries that already pay large sums into the EU, such as Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, Finland and Sweden, will make concessions or else face politically toxic increases in their payments.

Unknown factor:

It is unclear exactly how domestic politics would play out both in the UK and the Netherlands. In Britain pressure to pay nothing could result in worse long-term outcomes for the UK while, conversely, in the longer term if Britain was prepared to continue to pay into Brussels budgets it would win significant market access for less than its current £9 billion-a-year net contribution.

DATA

Worst case:

Huge amounts of personal data flow between computer servers in the European Union and Britain every day and the legal basis for much of this transfer will fall away in a no-deal Brexit. These flows of data allow online banking, e-commerce and the back-office functions of thousands of businesses to continue. In a no-deal scenario it will become illegal for European bodies to transfer such personal information to the UK. The EU has not yet made any contingency plans.

Best case:

The UK has said that it will legally recognise the EU as an “adequate” jurisdiction to hold the data of British citizens after Brexit. The EU has yet to reciprocate but it is unlikely to want to damage businesses that rely on UK servers to process information.

Unknown factor: The General Data Protection Regulation that governs the handling of personal data in the EU is policed by individual member states, which could interpret the rules differently. Any “patch” could be open to legal challenge."

I know what you mean. Some UK companies deserve to sink and if true capitalism was allowed to take its course they would - and resources would be funnelled elsewhere.I fully agree for JCB, a great company for this country to be very proud of.

My problem is how short we are of such gems and the often despair I felt when working for some of our poorer managed examples.

.

I could send in some stuff about Venezuela if you'd prefer. Another Socialist ideal gone wrong. What Socialists never quite get - is the moment you stop allowing markets to price goods things go terribly wrong.You really are a proper mouth breathing troll aren't you.

They think they can price everything from some central point and get it right - never happens - it just never happens.

FINAL PART:

DIVORCE BILL

Worst case:

Britain could end up paying more into the EU budget than under the financial settlement in the withdrawal treaty. The impact of no deal on the Brussels budget is low in 2019 because of the structure of the bloc’s financing, so the shortfall is only expected to be some €3 billion. The EU will demand payments in return for longer term measures, such as on road haulage of freight or aviation, and to ensure deals Britain would still have to make payments at least equivalent to the financial settlement in the draft withdrawal treaty — and possibly more. All 27 EU countries will have vetoes over many of the areas under negotiation and, according to senior Brussels sources, “will not even get around the table unless the money is there to stop a spending shortfall”.

Best case:

Money is seen as the key to unlocking a positive no-deal scenario by some hardline Brexit supporters. The EU will negotiate a good trade deal with Britain to avoid facing budget shortfalls of some €18 billion by the end of 2020 and a longer term loss of more than €20 billion in other payments. Money will be a lever for Britain because countries that already pay large sums into the EU, such as Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, Finland and Sweden, will make concessions or else face politically toxic increases in their payments.

Unknown factor:

It is unclear exactly how domestic politics would play out both in the UK and the Netherlands. In Britain pressure to pay nothing could result in worse long-term outcomes for the UK while, conversely, in the longer term if Britain was prepared to continue to pay into Brussels budgets it would win significant market access for less than its current £9 billion-a-year net contribution.

DATA

Worst case:

Huge amounts of personal data flow between computer servers in the European Union and Britain every day and the legal basis for much of this transfer will fall away in a no-deal Brexit. These flows of data allow online banking, e-commerce and the back-office functions of thousands of businesses to continue. In a no-deal scenario it will become illegal for European bodies to transfer such personal information to the UK. The EU has not yet made any contingency plans.

Best case:

The UK has said that it will legally recognise the EU as an “adequate” jurisdiction to hold the data of British citizens after Brexit. The EU has yet to reciprocate but it is unlikely to want to damage businesses that rely on UK servers to process information.

Unknown factor: The General Data Protection Regulation that governs the handling of personal data in the EU is policed by individual member states, which could interpret the rules differently. Any “patch” could be open to legal challenge."

That article was from the Times btw (a real Remainer paper if ever there was one btw)

Despite her complaining of it in parliament, I bet Andrea Leadsome has been sorely tempted to mutter it of rival deal backer Amber Rudd.Is it so difficult for us to not use sexist terms like "stupid woman"

.

This is awful news! I might not get my "Do it yourself Doom kit No Deal Brexit for Christmas!"

The polls are clear: support for staying in the EU has rocketed

For most of this year, polls have shown remain ahead of leave, typically by four to six points. But in a referendum between staying in the EU and leaving on the terms that the government has negotiated, staying enjoys an 18-point lead: 59-41%.

Still waiting for someone to come on with a decent agument in favour of Brexit being a good idea......Hello....is there anyone still thinks it's a good idea?

The polls are clear: support for staying in the EU has rocketed

For most of this year, polls have shown remain ahead of leave, typically by four to six points. But in a referendum between staying in the EU and leaving on the terms that the government has negotiated, staying enjoys an 18-point lead: 59-41%.

Still waiting for someone to come on with a decent agument in favour of Brexit being a good idea......Hello....is there anyone still thinks it's a good idea?

Is there a competition for the title going on?Despite her complaining of it in parliament, I bet Andrea Leadsome has been sorely tempted to mutter it of rival deal backer Amber Rudd.

.

Hmm even tommie thinks that is a funny idea!This is awful news! I might not get my "Do it yourself Doom kit No Deal Brexit for Christmas!"

The polls are clear: support for staying in the EU has rocketed

For most of this year, polls have shown remain ahead of leave, typically by four to six points. But in a referendum between staying in the EU and leaving on the terms that the government has negotiated, staying enjoys an 18-point lead: 59-41%.

Still waiting for someone to come on with a decent agument in favour of Brexit being a good idea......Hello....is there anyone still thinks it's a good idea?

You already know my feelings towards us using any terms others find offensive but I do also think the fuss made by media over this is quite ridiculous. I know quite a few people in media, it's a very prejudiced anti female industry, yet they are the very ones shouting loudest. Our country epitomises hypocrisy on so many fronts,unfortunately no more so than our politicians.Despite her complaining of it in parliament, I bet Andrea Leadsome has been sorely tempted to mutter it of rival deal backer Amber Rudd.

.

Surely there are more important issues to ask of Corbyn, and again to her credit May has hardly mentioned incident. . I, d guess she, s used to it...

Time to move on..

On a more general note...

OG, I can't really see point of conducting polls around leave or remain. Does anyone actually think we might get another chance to show our feelings.. I don't think so. Rather like studying holiday brochures when you ain't going on holiday. Rather pointless.

And on EU

Does anyone else think their entire campaign, rhetoric around our leaving has been completely wrong. Imagine filing for divorce and all your spouse can tell you is you won't cope and it will cost you more than me... It would only strengthen my resolve to go through with it. A better approach may well have been, look don't leave we need you and we really want you in EU with us..????

The whole approach has been regimented and authoritarian.

Notice Macron has given in on a few more issues. He, s not the Emporer he thinks he is...

Burning toll booths seems a good political move in France...

Last edited:

Here is the facebook Complaint document

https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/5637377-Facebook-Complaint.html

https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/5637377-Facebook-Complaint.html

Are you including yourself in that, or are you making an exception in your own case as usual?Time to move on

Just what I've been saying for a while now. It's why the Leavers are so terrified of another referendum, knowing they'd lose this time.For most of this year, polls have shown remain ahead of leave, typically by four to six points. But in a referendum between staying in the EU and leaving on the terms that the government has negotiated, staying enjoys an 18-point lead: 59-41%.

.

Hmmm...so the Irish have blinked first - the Brussels Mafia won`t be pleased!!

UPDATE: Irish Government Minister appears to let the cat out of the bag that checks away from the land border would work

Ireland have once again confirmed that they have no plans to erect a hard border on the island of Ireland even if there is no Brexit deal. The Irish Government published their contingency planning for no deal yesterday, with Foreign Minister Simon Coveney confirming that Ireland has no plans to build a hard border in the event of no deal. The backstop is spurious – there is not going to be a hard border whatever happens…

The EU have shot themselves in the foot over this one. They and their puppets Leo and Simon insisted that the backstop was the only solution, but here we have a solution to the Irish border which doesn't involve a hard border or annexing Northern Ireland.

This will be held up by Brexiteers as proof that the EU was playing political games over the NI border issue all along and Theresa May fell for it.

UPDATE: Irish Government Minister appears to let the cat out of the bag that checks away from the land border would work

Ireland have once again confirmed that they have no plans to erect a hard border on the island of Ireland even if there is no Brexit deal. The Irish Government published their contingency planning for no deal yesterday, with Foreign Minister Simon Coveney confirming that Ireland has no plans to build a hard border in the event of no deal. The backstop is spurious – there is not going to be a hard border whatever happens…

The EU have shot themselves in the foot over this one. They and their puppets Leo and Simon insisted that the backstop was the only solution, but here we have a solution to the Irish border which doesn't involve a hard border or annexing Northern Ireland.

This will be held up by Brexiteers as proof that the EU was playing political games over the NI border issue all along and Theresa May fell for it.