If history is an indicator, we are in this for the long haul. In spite of our most fervent wishes to get outside and enjoy the rites of spring—college graduations, Mother’s Day, youth sports—life is unlikely to return to normal anytime soon. The great influenza of 1918, considered the deadliest pandemic in modern history, offers a social distancing roadmap for tackling today’s COVID-19.

After Philadelphia detected its first case of flu in September 1918, leaders warned people about openly coughing and sneezing, but ten days later the city hosted a parade attended by 200,000 people. The number of influenza cases continued to mount, and two weeks after the first case there were 20,000 more. Several cities (St. Louis's Red Cross motor poll is shown above) responded quickly and decisively—and had a strikingly lower initial death rate.

As the world grinds to a halt in response to the coronavirus, scientists and historians are studying the 1918 outbreak, which killed 675,000 Americans and from 50 million to 100 million people worldwide, for clues to the most effective way to stop the pandemic.

St. Louis strictly communicated and enforced social distancing, giving it one of America’s lowest urban death rates when the outbreak, known as the great influenza, swept the nation (and the world). Minneapolis, Milwaukee, Indianapolis, and Columbus, Ohio, did the same thing—and had lower death rates the first few months.

But that’s not the takeaway—because St. Louis relaxed. It declared victory too soon.

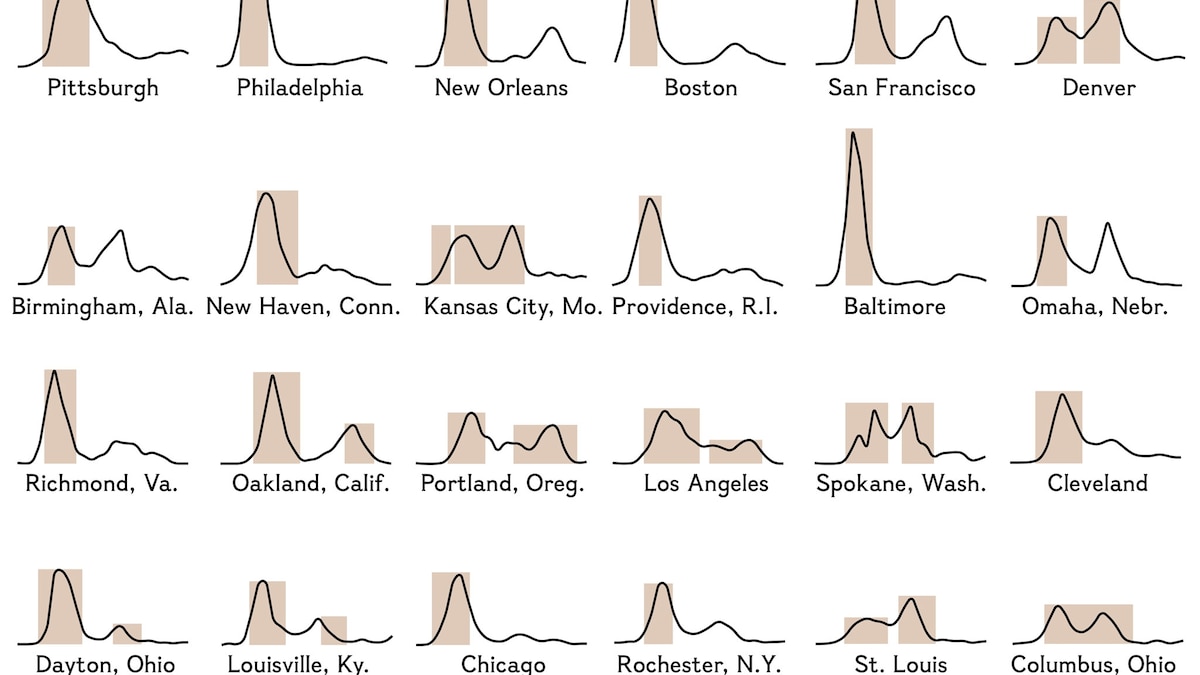

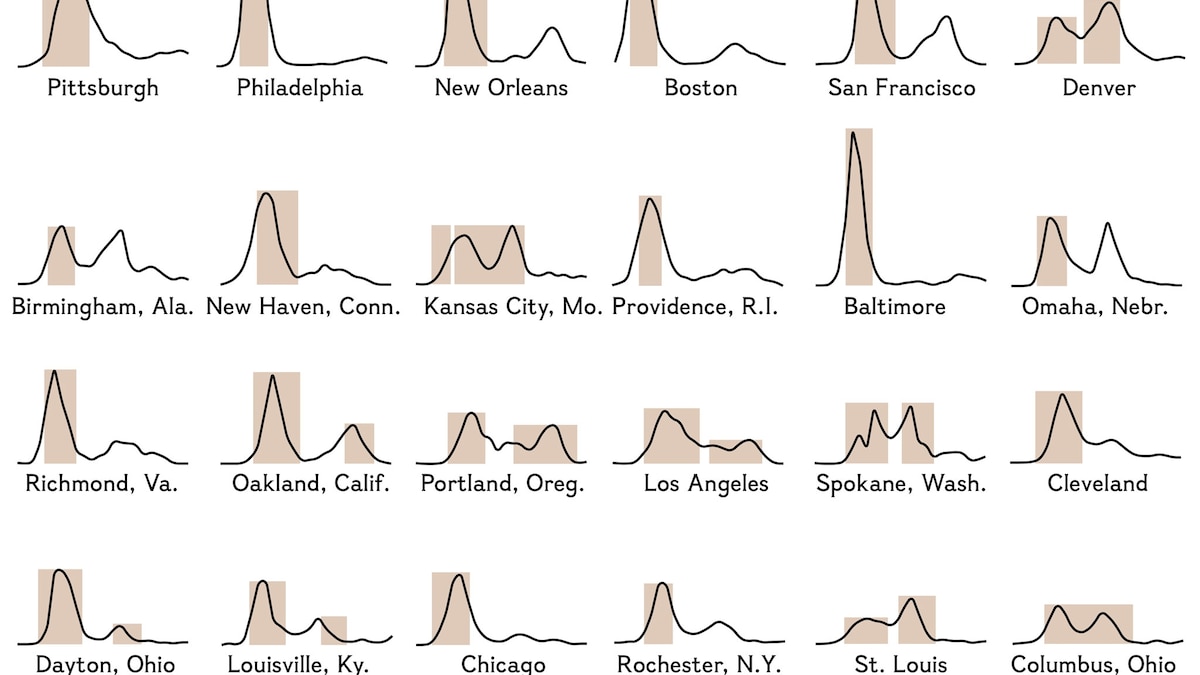

That second bump in this graphic above shows the influenza's tragic reoccurrence in St. Louis, writes Nat Geo’s Nina Strochlic. Death rates shot up, higher than before.

The lesson from history–don’t cave to a restless, pent-up, impatient populace; it could be fatal. Even as the beauty of spring comes into bloom, keep your distance!

www.nationalgeographic.com

www.nationalgeographic.com

After Philadelphia detected its first case of flu in September 1918, leaders warned people about openly coughing and sneezing, but ten days later the city hosted a parade attended by 200,000 people. The number of influenza cases continued to mount, and two weeks after the first case there were 20,000 more. Several cities (St. Louis's Red Cross motor poll is shown above) responded quickly and decisively—and had a strikingly lower initial death rate.

As the world grinds to a halt in response to the coronavirus, scientists and historians are studying the 1918 outbreak, which killed 675,000 Americans and from 50 million to 100 million people worldwide, for clues to the most effective way to stop the pandemic.

St. Louis strictly communicated and enforced social distancing, giving it one of America’s lowest urban death rates when the outbreak, known as the great influenza, swept the nation (and the world). Minneapolis, Milwaukee, Indianapolis, and Columbus, Ohio, did the same thing—and had lower death rates the first few months.

But that’s not the takeaway—because St. Louis relaxed. It declared victory too soon.

That second bump in this graphic above shows the influenza's tragic reoccurrence in St. Louis, writes Nat Geo’s Nina Strochlic. Death rates shot up, higher than before.

The lesson from history–don’t cave to a restless, pent-up, impatient populace; it could be fatal. Even as the beauty of spring comes into bloom, keep your distance!

How they flattened the curve during the 1918 Spanish Flu

Social distancing isn’t a new idea—it saved thousands of American lives during the last great pandemic. Here's how it worked.